A Revisit of Jean François Revel’s 1970 book, Without Marx or Jesus: The New American Revolution Has Begun

©Philip J. Hohle, Ph.D.

A battle is being fought . . . the stakes are of the utmost importance for all mankind . . . . It is absolutely necessary if mankind is to survive. The exchange of one political civilization for another, which . . . seems to me to be going on right now in the United States. -Jean François Revel, 1970

These are the words of French socialist Jean-François Revel in 1970. He believed that a unified world order would be the result of this revolution, and the impact would finally sweep the world of regressive and harmful ideologies. He was remarkably prophetic in how the revolution was to progress.

There are five revolutions that must take place either simultaneously or not at all: a political revolution; a social revolution; a technological and scientific revolution; a revolution in culture, values, and standards; and a revolution in international and interracial relations” (162). The result would be, “The abolition of war and of imperialist relations by abolishing both states and the notion of national sovereignty; . . . world-wide economic and educational equality; birth control on a planetary scale [read: abortion?]; complete ideological, cultural, and moral freedom (Revel, 161).

According to Revel, this revolution would necessarily have the United States as the epicenter of this change. In his book, Revel prescribed a comprehensive transformation of American culture. The accomplishment would come to pass, not accidentally, but as the matured cumulation of the many isolated, incomplete, or failed revolutions attempted in Europe, Asia, Latin America, and in other parts of the world. Socialist revolutionaries, Revel insisted, would finally get it right in the revolutionizing of the United States. This reformed America would then lead the rest of humanity into a better world-where romantic fascinations of the colonial, imperialistic past would finally be put aside in order that true equity would be enjoyed by all. A new world authority will take the place of autonomous national governments. Personal property would be shared with all.

Revel predicted this new revolution half a century ago. Many of the necessary social transitions have indeed come to pass in a series of small steps that may have gone unrecognized as a part of a unified effort. If so, let me be the first to welcome you to this new world order. Perhaps you did not realize you had boarded that train, but we are indeed pulling into the station just now. This journey and destination is the very progress dreamed of by those who call themselves Progressive. Their long march is almost over; their goal is within sight.

Jean-François Revel was a disciple of classic liberalism, ideals that seem today almost conservative in comparison to some of the radical notions of the far left. Due to their numerous historical failures, Revel shared his many revealing observations concerning the radical wing’s fallacies. Yet, in spite of the harsh criticism of his fellow socialists, Revel’s intention was clearly constructive. His book was to help make the revolution more inevitable, more potent.

Specifically, Revel noted that the passionate leftist revolutionaries often destroyed the countries they aimed to claim. After the overthrow, they found themselves incapable of replacing or rebuilding the necessary institutions that serve the populace. In pointing to history, Revel asserts that such failed revolutions have only invited dictators and oligarchies to rise from beneath the chaos.

“No more!” Revel exudes his reader, “This time we will succeed! We will bring the institutions down to their knees, but we will transform them, not destroy them. We must keep alive and master the goose that lays golden eggs” (paraphrased).

American revolutionaries, in effect, are in an ideal situation. They are the beneficiaries of the system of whose failing they denounce (Revel, 179).

The American system of government is seen as especially ripe for overthrown due to the freedoms outlined in the constitutions and proactively enforced by our courts. Thus, the revolution would not require the violent measures tried elsewhere; the American revolution would be conducted through legal means. Moreover, Revel marveled that he knew of no other society that would allow members of the police or military to stand trial for the execution of their duty.

The best return on violence is achieved by its marriage to the legal resources offered by America’s political system (Revel, 200).

Fifty years later, Americans are in the later stages of Revel’s prophesied revolution. Of course, were it not for the unexpected election of Donald Trump, the revolution might simply have been about the business of mopping up in the year 2020. The question arises; will progressives be ultimately and wholly successful in achieving the final goals for the revolution in light of the political setback? Even if the COVID-19 crisis helps bring down the Trump White House, will the economy recover after the sweeping socialist protocols of pandemic are finally relaxed?

In any case, it is yet to be seen if today’s progressive revolutionaries can prove that they can overcome their weaknesses. In their zeal, they may actually destroy what makes America great and worthy of claiming.

The many societal changes in America since 1970 indicate that these revolutionaries may have indeed learned their lesson-they have been extraordinarily patient and strategic in their efforts. History shows that these progressives have made remarkable progress in transforming the country in measured steps, puzzle piece by puzzle piece.

A reading of Revel provides proof that each change was part of a plan- subtle, intentional, and unified. For at least fifty years, a conspiracy has indeed been underfoot. Without the patient being fully conscious to the transfusion of ideology, the citizenry of this country have been hooked up to the ideological dialysis machine for decades. Drip by drip, for better or for worse, today’s America is no longer like the America of Revel’s day.

Over this span of time, American leaders warned people of an oncoming military conflict with the communists-like the one played out in Vietnam. In spite of the vigil, and without a shot, a communist-like revolution has mostly succeeded in gaining control of the US in spite of the vigilance. The revolution’s quiet victories have been won partially because they avoided raising the population’s concern over Marxist imperialism-the Red Scare that shook Americans in Revel’s time.

The [new] American revolution is, without doubt, the first revolution in history in which disagreement on values and goals is more pronounced than disagreement on the means of existence (Revel, 134).

Furthermore, the revolution progressed without the need for the socially woke version of Jesus imaged by the liberal wing of Western religion over the same decades. Certainly, conservative American Christianity had to be sidelined early to make space for a brand new morality.

Above all, we must know what is the “threshold of perception” of disaster within a society; we must know the danger signals, and we must know the controls by means of which this information can be translated into political action (Revel, 97).

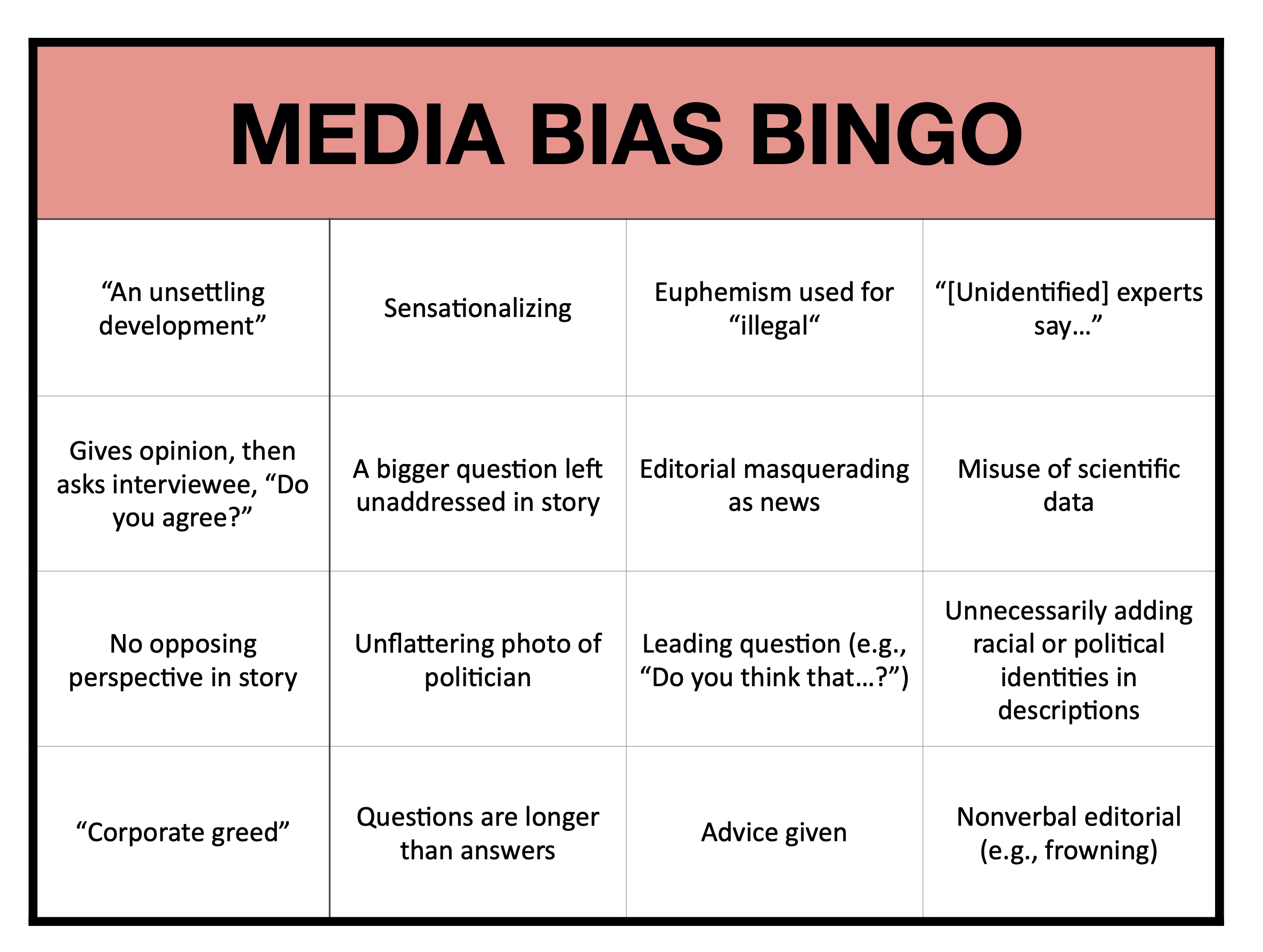

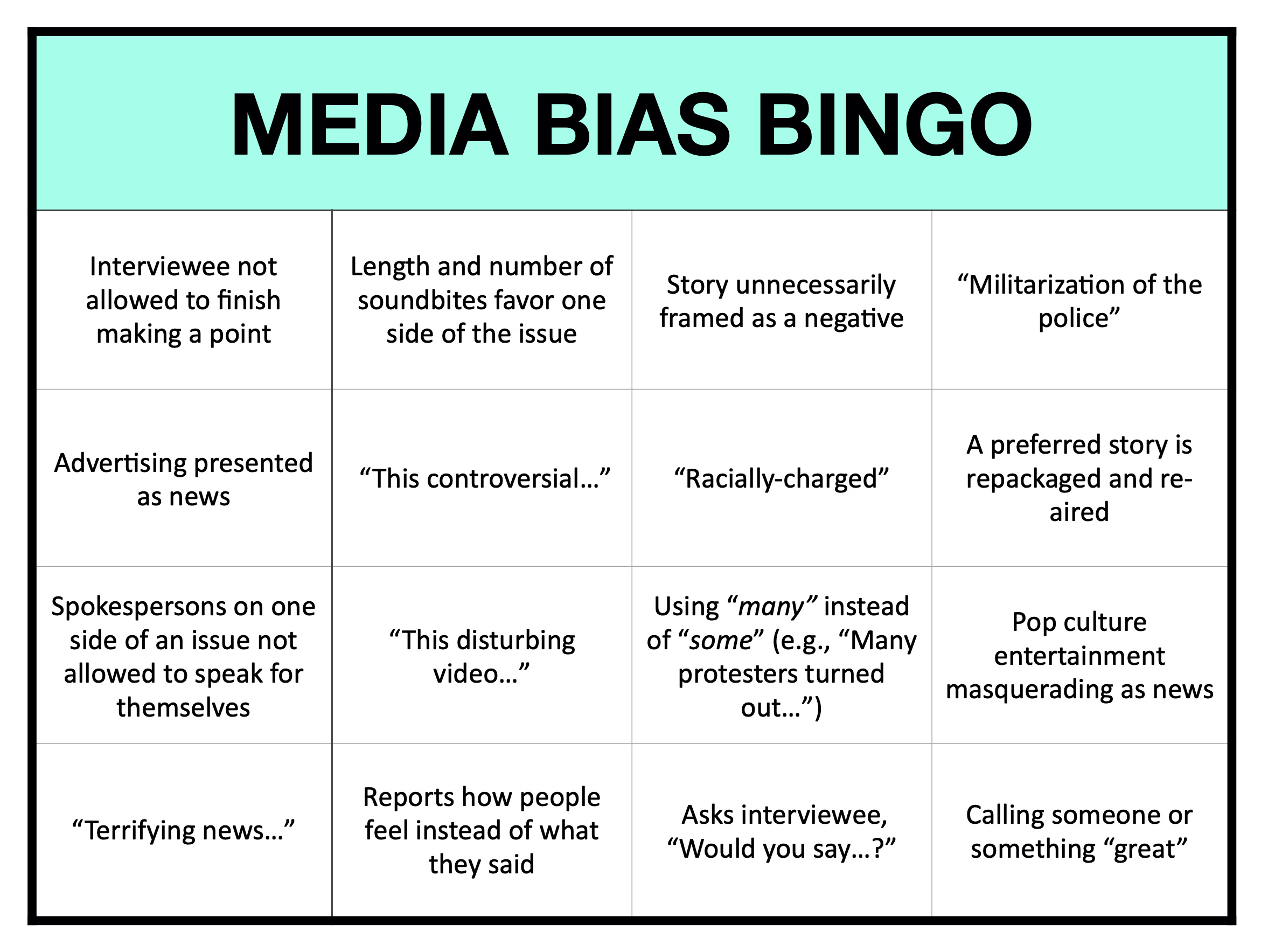

One may wonder what perceptions of disaster have come upon us in the last several decades-what dire warnings have been translated into political action? One can clearly recognize an alarmist agenda in the media, sensationalism that serves to promote a perception of impending doom. Shows like The View, The Daily Show, and even Good Morning America are (or were) popular programs where episodes feature passionate warnings about certain calamities that will likely destroy viewers unless they take immediate action.

The Disastrous Dozen

Over this last half-century, those heralds of disaster have cried warnings on an entire range of impending catastrophes facing all Americans. Each crisis provided an opportunity to weaken further the American resolve or ability to resist. What follows below are several crises that have faced Americans over the decades, and the possible aftermath of those emergencies.

1. Overpopulation.

The specter of unrestrained human population growth was painted for us in books like Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb (1968). More than just overcrowding, overpopulation fuels the side effects of war, disease, and famine. The crisis served to shake the foundations of the traditional family unit and open the door to using abortion as a means of birth control. Alarmed readers were warned not to be fruitful or multiply.

2. The rise in fascism.

Providing evidence that Nazis were still active among us, the revolution precipitated a crisis that was used as a means to further cripple prideful nationalism and to cancel, or reclassify as a xenophobe, anyone who would still dare to call themselves a patriot. Meanwhile, the historical atrocities of communists patriots were conveniently forgotten or downplayed.

Is it progress if a cannibal uses knife and fork? (Polish Poet Jerzy Lec Stanislaw)

3. The Christian Moral Majority’s attempt to sway the government.

Comparing the movement to the Salem witch-hunts, the backlash was used as a means of removing the Church and God as competing moral authorities vying for the souls of Americans. Ironically, we have seen the Moral Majority’s Judeo-Christian ethic swapped out with the revolution’s Neo-Puritan strict morality, a political woke-ness bereft of grace and forgiveness.

[The revolution has] resulted in a widespread and strong feeling of guilt and a passion for self-accusation, which, on occasion, tends to go to extremes (Revel, 134).

4. The attacks by the far right on the free press and the rising specter of censorship.

This crisis was a way to claim the high ground of the venerated First Amendment. It served to belittle the cries of “wolf,” from those conservatives who would use prior restraint to quiet speech they feared represented a clear and present danger to the ideals of democracy and the security of the state. Another inversion was accomplished; instead of protecting American’s free practice of religion, the First Amendment has now become the very weapon used to shield Americans from religion’s influence. Replacing sedition as a primary concern, religion became the clearest and most present danger in need of censorship. Today, we amplify voices that protest while we silence those that proselytize.

This spirit of criticism of values, which is more emotional than intellectual, is made possible by a freedom of information such as no civilization has ever tolerated before (Revel, 134).

5. The immigration crisis.

The problem at the border is no longer framed as an issue of security or the war on drugs. The revolution repackaged the problem as a moral issue concerning the plight of innocent mothers and children fleeing gangs and oppressive governments. In turning our eyes from the gate, this crisis served as a way to import many more soldiers of ideological change who will dilute the concentrations of conservative resisters in key states. Without a secure border wall, there is no immigration problem. And of course, without a viable border, there can be no more delusions of sovereignty.

Real revolutionary activity consists in transforming reality, in making reality conform more closely to one’s ideal, to one’s point of view (Revel, 104).

6. The failures of our educational systems to keep pace with the world.

This failure precipitated a move to shed regressive ideology from the curriculum and to further remove parents as the primary influencers in children’s lives. No longer will the revolution allow the local community to have any authority in making choices on the curriculum for their schools. Meanwhile, conservative thought has been all but banished from the university classroom. Most universities today are more like an intellectual desert than a garden of ideas. Students are allowed to take only those positions pre-approved by the revolution on any subject. Intense norming pressures from faculty and other students inhibit the broad-minded scholar from challenging the nonsense that is served up as good, beautiful, or true.

Revolutions are not measured by the things that are done, but by the things that are prevented and by those that are allowed to happen (Revel, 164).

7. Homophobia and intolerance toward alternative lifestyles.

This crisis is found in the battle over what can be considered ethical and what is perverse. In a stunning reversal, the revolution has tried to demonstrate the immorality of Bible-based intolerance toward people with alternative lifestyles. In advancing the disproportional eminence of the LGBTQIA (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual) culture, progressives have sought to emasculate the heterosexual father’s role in the family. Meanwhile, sexual predator behavior with minors is still deemed perverse when discovered among Catholic priests, but the exact same thing is called “helping a young person figure out a sexual identity” when the enlightened perpetrator has no religious pretensions.

The forces of change exist in an atmosphere of constitutional benevolence . . . . The more that chance is possible through legal means, the better the chances of revolution (Revel, 163).

8. The inconvenient truth about climate change.

Since the revolution’s goals include the redistribution of wealth, this crisis has served as an effective means to generate guilt in Americans over their materialistic privileges-the giant carbon footprint left by Western capitalists on the fragile throat of the world’s limited resources. Fear and shame were evoked without raising any of the usual red flags created by the typical envious Marxist blustering concerning private property.

9. Toxic masculinity.

The new world order has no room for warriors since war will be a thing of the past. As they remove the remaining distinctions between right and wrong, feminists ideologues are teaching our boys to forget their irrational instinct to defend women and children against evil. Joining the war against paternalism, progressives in the mass media will successfully eliminate positive examples of strong manhood that boys might use as a pattern for their lives. The cowboy has already become a caricature of himself, the policeman has become corrupt and racist, and the soldier no longer has a noble cause worthy of defending. The father has become just another mother in the home-he is better at baking bread than winning it. Family Guy and Homer Simpson clearly demonstrate this new man’s role in society. This cartoon-like husband/father/warrior is worthless. His only redeeming quality is that he can be entertaining-relegated to play the role of the clown. As such, he is the sole demographic the enlightened progressive can ridicule without guilt.

There is an apparent nonviolence, which is really more violent than an act of spectacular brutality (Revel, 105).

10. Deadly worldwide pandemics.

Not likely planned events (at least we can hope not), these crises still serve to demonstrate the ineffectiveness of sovereign nations and their borders while creating a dependency on world authority. Mandates on quarantines and mask requirements, while arguably helpful in combatting the disease, may also serve as a beta-test for more state-sponsored control in the future.

11. The militarization of the police.

This crisis provided an opportunity to shuffle the rails of the fence by installing a new sheriff in town. Polish Poet Jerzy Lec Stanislaw had this to say in reference to the changing of the rails, “When smashing monuments, save the pedestals. They always come in handy.” Embolden by their moral superiority in condemning and canceling any historical leader deemed brutal or racist, the new mounted figure celebrated on the monument will be the same revolutionary who tore down the old one. Once fully in charge, the militarization and brutality of police-work will not disappear. The new policing authority will use similar strong-arm methods to put down any person of means who tries to protect their private property or dares to voice disapproval of the revolution.

The police always accuse dissenters of “terrorism” and “armed violence”-unless the dissenters beat the police to the punch and accuse them of the same thing (Revel, 111).

12. The spread of racism.

Perhaps the most brilliant strategy of all, progressives have hidden their revolutionary intentions behind the American crisis of shame and guilt over racism. The ploy to re-stoke the conflict over civil rights from the 1960s has proven an effective method to further silence and cancel the resistance. It was ironic that Revel himself did not see in America the kind of inherent racism seen in other parts of the world-even with the racial tension still resonating in the US in 1970 when he wrote his book. Nevertheless, when the revolutionary can make the resister feel shame, they will naturally seek relief from their guilt. The brilliance is this: In this current crisis, no other source of absolution is possible except that from the revolution itself. The only reparation worthy of exoneration is one’s full loyalty to the revolution.

Paradoxically, the United States is one of the least racist countries in the world today . . . . The demands of black Americans are, after all, more cultural demands than class demands (Revel, 202).

The End of the Long March?

The conspiracy-minded among us will sense that all of these were planned disasters selected and employed as means to the goals of the revolutionary. They will note that each and every time, well-meaning Americans responded to the crisis without first questioning it. The more skeptical among us may simply consider these changes a part of natural evolution, growing pains as it were, and that these alarms were indeed in response to real wolves at the door. In either case, what is unmistakable is the truth that each disaster has changed America in some fundamental way.

One such fundamental change is the way Americans perceive freedom. The present generation of Americans seem bent on claiming the maximum of personal freedom in behavior and expression at the cost of community. Perhaps one residual fallacy of the left’s approach is that one cannot claim a right to diversity while striving for unity within the community-an ideological contraction Revel recognized even in the revolutionaries of his day. While he saw this growing liberty as an indispensable foothold for the revolution, he also admitted that the practice of freedom could create new inequities he called “imperfect and unjust.”

The revolutionary ideologue may find a loophole in the paradox of liberty if they perceive this indispensable personal freedom like a tethered climber on the face of a cliff. The climber is allowed the freedom to move, but only in the desired direction. In the case of this new revolution, personal freedom is encouraged only when it advances the dismantling of resisting institutions. Two examples; the revolutionary has absolute freedom to blaspheme the sacred tenants of the church, but the Christian who voices his defense is labeled an intolerant bigot. Likewise, the heroic revolutionary is encouraged to use her personal freedom to practice civil disobedience in disturbing the peace of the community-closing public roads and buildings and creating autonomous zones. On the other hand, law-minded authorities are handcuffed in holding this activist accountable for the damage she inflicts. One action enjoys liberty, while the other is restrained.

Today, the disruptions caused by the excesses of personal freedom trump the peace that comes from unity under the law. This revolutionary stance seems to contradict the kind of egalitarian society, where people willingly sacrifice their rights for the good of the community. The tether is this: Personal freedoms are granted only if they directly support the revolution-and of course, if you practice your freedom in a way that selfishly opposes the revolution, your personal freedoms will be restricted. If and when the revolution becomes the status quo, those personal freedoms will be curtailed, and individualism will again be seen as a threat to the new world order. History is sure to repeat itself in this regard.

American revolutionaries do not want merely to cut the cake into equal pieces; they want a whole new cake (Revel, 134).

These American revolutionaries have won many victories along the way in their long march toward domination, but they have done so in spite of their many illogical contradictions and any valid proof of concept. Again, Stanislaw wrote, “Once it is given the chance, a dream will always triumph over reality” (paraphrased). Still, one may have reason to wonder if the dreamy leaders of this new world order will ever claim their full sovereignty.

Liberation must be complete, or it will not exist at all (Revel, 179).

Perhaps a new breed of counterrevolutionaries is right now strategizing ways to make the progressive liberation incomplete. In their own way, conservatives may be woke in a rising call to regain some of the socio-political ground lost over the last fifty years. If such opposition is mobilized, will they fall back on the use of armed resistance like have so many other insurrectionists in our world’s history? Or will they have the same patience of Revel’s progressive revolutionaries to sequence a number of quiet-but-strategic battles over time?

Even without the opposition of an organized counterrevolution, perhaps those exuberant progressive revolutionaries, in the end, will stumble over their emotionally infused contradictions. After the goose produces no more golden eggs, will their dream die in the sobering light of facts and sound logic? In either case, it may yet take another half-century to see if Revel’s promised revolution is finally completed.

Revel, Jean-François Revel. Without Marx or Jesus: The New American Revolution Has Begun. New York: Dell Publishing (1970).